|

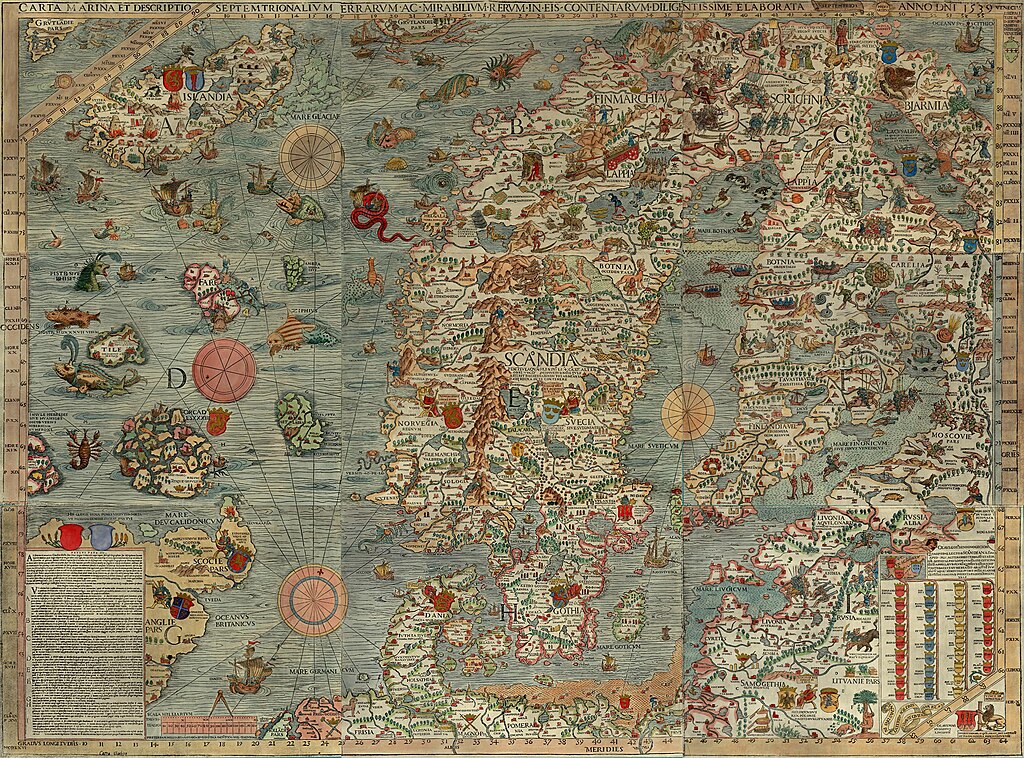

| Monsters and maps. (Click here for an interactive version.) Olaus Magnus, Carta Marina..., 1539. |

The full name of the map is: Carta marina et Descriptio septemtrionalium terrarum ac mirabilium rerum in eis contentarum, diligentissime elaborata Anno Domini 1539 Veneciis liberalitate Reverendissimi Domini Ieronimi Quirini ("A Marine map and Description of the Northern Lands and of their Marvels, most carefully drawn up at Venice in the year 1539 through the generous assistance of the Most Honourable Lord and Patriarch Hieronymo Quirino"). It was the first map printed in the south of Europe to show extensive and accurate detail as well as place-names. Olaus Magnus also penned a book titled Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus ("A Description of the Northern Peoples"), which was printed in 1555.

Scholar Joseph Nigg has just released a book about the Carta Marina with the University of Chicago Press called Sea Monsters: A Voyage Around the World’s Most Beguiling Map. The online newsmagazine Slate has posted a short introduction to the map, complete with a fully zoomable and clickable depiction of some of its monstrous creatures.

Chet Van Duzer, a scholar at the Library of Congress, has also recently published a book about sea monsters on maps titled, Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps. As Van Duzer notes: "The creatures look purely fantastic. They all look like they were just made up. But, in fact, a lot of them come from what were considered, at the time, scientific sources."

- "Here Be Duck Trees and Sea Swine: An interactive Renaissance map filled with strange and wonderful monsters," Slate, by Joseph Nigg

- "Here Be Dragons: The Evolution of Sea Monsters on Medieval Maps," LiveScience, Tanya Lewis

- "The Enchanting Sea Monsters on Medieval Maps," Smithsonian.com, Hannah Waters